Remembrance weekend 2021 saw the Shildon Heritage Alliance CIC reveal the findings of their year long project to bring to light the stories of 250 male and female members of Shildon Railway Institute who served during WWI and whose names are commemorated on a war memorial that was installed in the Institute early in 1921.

What’s unusual about the memorial is that 220 of the persons named survived and lived on, so have stories that extend beyond the war. Many of them, including six nurses, went on to raise families many of which are still represented across the town today.

The reveal event, which took place on Saturday 13th November, at the Institute, also featured a talk by historian Rob Langham on the North Eastern Railway during WWI. It had also been intended to feature a concert by the Durham Miners Association Brass Band featuring the work of Shildon born composers George Allan and Tom Bulch whose sons served during that conflict, however that element of the event had to be cancelled at short notice owing to an outbreak of Coronavirus in the band.

Another concession to the virus on that day was the address scheduled to be given by Shildon Heritage Alliance CIC Director Dave Reynolds, though SHA/SOS volunteer Samantha Townsend was able to step in to deliver the address on his behalf. The address to those present was as set out below.

Three physical copies of the findings of the project were made available for members and visitors of the Institute to read – and a digital copy was published on the Shildon Railway Institute website. This is intended to be a living project and as new information comes to light it will be updated and republished. You can view the digital copy here: https://shildonrailway.institute/heritage-1/wwi-memorial

_______________________

Address on the hundredth anniversary of the Shildon Railway Institute war memorial.

Dave Reynolds: Director & Volunteer of the Shildon Heritage Alliance CIC

Today I’m here to talk to you about a project that has been a year in the making on our part.

I’m doing that as a Director of the Shildon Heritage Alliance which is a Community Interest Company that was set up in 2019 principally to work with the Committee of Shildon Railway Institute to work to keep breathing life into this great and oldest of Railway Institutes which is now in its 188th year.

It also exists to champion other pieces of Shildon’s heritage that fall into the gaps left by other groups and organisations large and small are interested in.

We are an organisation of about fourteen volunteers, with various skills and abilities, and nobody within the SHA ever receives payment for any the work we do.

What we do, we do out of love for this community and its past, present and future.

A primary goal for the SHA is to try to ensure that Shildon Railway Institute can be here for this community for another hundred years, and to move towards renovation and preservation of this iconic Shildon landmark.

We paid to have a condition survey conducted during 2020 that suggested that

A key stage that must be achieved on this journey is to prove to would-be funders, like the National Lottery, that this Institute is here for, and actively used by, as many parts of our community as possible.

I cannot deny that the Coronavirus pandemic has set us back on that mission.

But we’ve also been pleased to have welcomed new groups that want to make Shildon Railway Institute their new home. These include:

Shildon Railway Institute Football Club

The recently reformed Shildon Branch of the Royal British Legion

The Shildon Institute Singers

We, and the committee, are also pleased to have welcomed back the groups that use the institute for fitness sessions, bingo and midweek dancing.

Our Institute Women group (not to be confused with the Women’s Institute) has been doing tremendous work to bring different activities and experiences to the place.

There is room however for much, much more so please speak to us if you have a group or organisation in keeping with out values that needs an occasional home for activities.

Another thing that we have to be able to do is to prove to would-be funders that we recognise and are capable of looking after what we have.

This is something that this Institute in latter decades has forgotten to do.

One of the things the SHA has tried to do in that respect is help financially and physically with spruce ups of parts of the building to help to make them more enjoyable to use.

It was with this in mind that in October last year I looked at the Railway Institute Members War Memorial on our main stairwell and decided to try to clean it up a little.

That in itself took me around thirteen hours of work with Brasso and a dozen dusters.

As you can imagine – in that space of time I had plenty of opportunity to get to know some of the names quite intimately.

And that got me thinking.

Who were these thirty men who laid down their lives for king and country?

And who were the 220 lads and lasses named that also served?

What was their connection to the Institute – and what could that tell us about the Institute at that time?

We decided to set up a project to learn what we could about the memorial – and the men and women named.

That was when we quickly learned that the memorial would be 100 years old this year.

But before I tell you something of what we learned – I firstly want to thank the people that contributed a great deal, or a little, time to this endeavour.

They are:

- Dawn McArdle

- Kelly Ambrosini who tried to keep us all co-ordinated

- Michelle Armstrong and her dad Bill Armstrong

- John Raw

- Trevor Horner

- Catherine Howard

- Lisa Knight

- Pauline Buddin

The memorial, is an arrangement of three plaques

It was created through family and member subscriptions and was ordered from a company called Jones and Willis who specialised in such memorials.

They were a Birmingham firm who manufactured church furnishings – one of the biggest firms of this kind in the latter part of the nineteenth century. They also opened premises in Liverpool and in London.

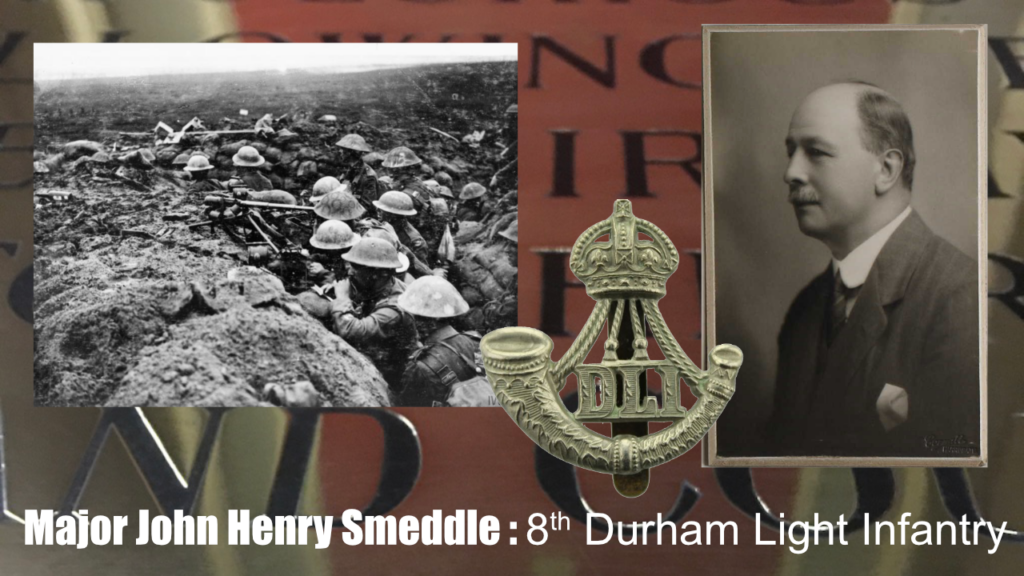

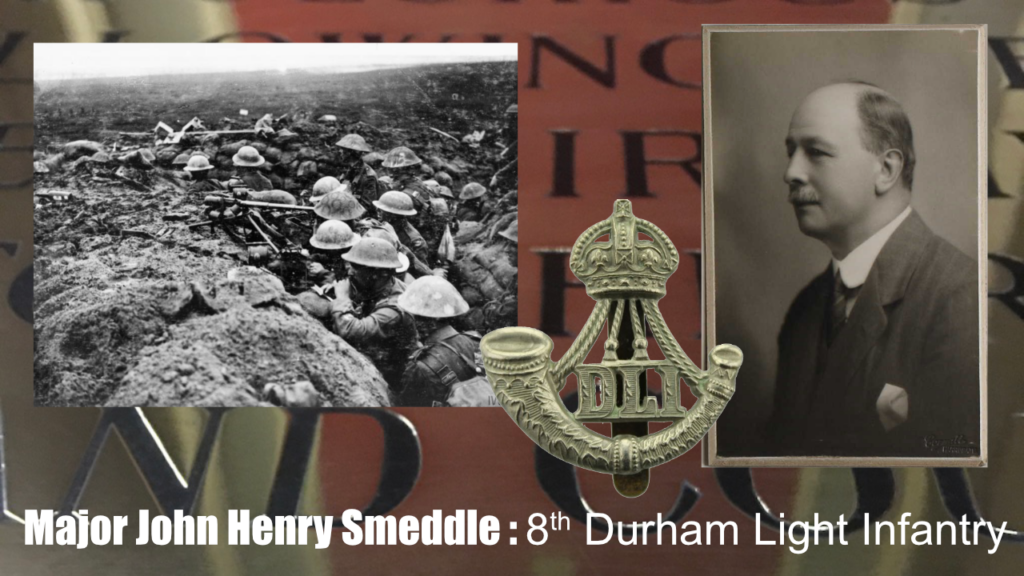

These plaques were installed then unveiled and dedicated on the 8th November 1921, with New Shildon born John Henry Smeddle and Archdeacon Derry in attendance.

Why John Henry Smeddle?

John was born in New Shildon in 1866 – and was the son of Dr Robert Smeddle, a well known figure of the town.

He grew up on Magdala Terrace. He became an apprentice in the North eastern Railway in 1882 and pupil of the Engineer of its Central Division.

He became a foreman at Scarborough and Inspector at Gateshead and by the end of the nineteenth century he had become Assistant Area Locomotive Superintendent for the North Eastern Railway and had been inducted into the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.

But his life had been touched by the war. He was mobilised in 1914 and served in France in 1915 and 1916 attaining the rank of Major and becoming 2nd in Command of the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry while the battalion fought at Ypres, Armentieres, Kemmel and the Somme.

He was probably the most senior Shildon born soldier to have served in that conflict – and would have been well known in the town.

________

To find out something about the other soldiers and nurses named, we used a variety of sources.

- Much of the information in this document was drawn from information available at the following websites

- Ancestry

- Fold3

- BritishNewspaperArchives

- The British National Archives

- The Red Cross

Additional sources included:

- A list of Shildon Works NER employees and enlistment details available from the Head of Steam Museum at Darlington

- North Eastern Railway Magazine (1914-1919)

Censuses of particular interest:

- The 1901 Census – which was taken on 31st March 1901

- The 1911 Census – which was taken on 2nd April 1911

- The 1939 Register – which was taken early in the 1939-45 war on 29th September 1939

But what did we learn?

Well, the answer to that is a great deal – and not always what we expected

Firstly – the hardest thing we had to learn – beyond the harrowing tales of soldiers lives – was that we will probably never get to know everything we wanted to about every name.

This was in part because in September 1940 a fire caused by an incendiary bomb at the War Office Record Store in Arnside Street, London, destroyed approximately two thirds of 6.5 million soldiers’ documents from the First World War.

The records which survived were mostly charred or water damaged and unfit for consultation and became known as the ‘burnt documents’. The surviving ones were digitised from 1996 onward.

Not only that, but we were also very reliant on snapshots in time – the censuses.

These are taken every ten years and a great deal can happen in between – people come to Shildon and leave Shildon and the evidence is not always there.

There were probably fewer than twenty that we were unable to identify – though none of these were the men who lost their lives.

We have not given up hope on those names. We think the 1921 census released next year might offer us some more clues.

The next big thing we learned was that we went into this exercise expecting most of these men to have served in the Durham Light Infantry.

The men, specifically, on this memorial served in a wide range of regiments

Perhaps one of the biggest intakes from Shildon at the beginning of the war was into the Royal Army Medical Corps. These were the brave lads who would risk their lives to retrieve casualties from the battlefield and get them to the safety of the field hospitals.

The North Eastern Railway had long had an ambulance movement with classes and competitions.

Many of the lads who were part of this movement were signed up as military reservists before the war, and were mobilised in the early stages.

There were indeed many of the men who joined the Durham Light Infantry pioneer battalions who particularly sought the labour of swarthy fit young men.

But the military unit most associated with the railway workers was the 17th Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers which was a ‘pals’ battalion into which men of a common working background could enlist to fight together.

That said it would be incorrect to say that these men enlisted into either one of the other of these Regiments

They were spread right across the military units.

- The Seaforth Highlanders

- The Green Howards

- The Kings Own Liverpool Regiment

- The Sherwood Forresters

- The Coldstream Guards

Men went to units that needed them.

Many with experience of running locomotives were taken into the Royal Engineers Railway Operating Division – and with the Shildon Works in living memory its easy to forget that Shildon had a large locomotive department too. Their experience was essential in getting supply trains across Europe and North Africa.

Many joined the Royal Field Artillery, or the Royal Garrison Artillery.

There were more specialist roles such as with the Remounts, sourcing horses to send to the battlefront – as anyone who has seen War Horse will recall.

Though most joined army battalions there were others that became seamen or joined the fighting naval battalions.

And we must not forget that it was during this conflict that a new form of aerial warfare was introduced, and there were a handful of Shildon Institute men whose mechanical skills were welcomed into the newly formed Royal Air Force to help keep flying machines airworthy.

Then of course there were the nurses – and we must be particularly grateful that this memorial includes the names of six volunteer nurses – often overlooked – a couple of which went on to make a lifetime career in nursing after the war.

Something else that we learned that really surprised us is what these young men and women did in their civilian lives.

We have often been told that Shildon Railway Institute was a place for the men of Shildon Works and their families – we know that this was not exclusively the case.

We have seen from early membership books that the membership of this Institute, despite its having been created by Railway officials, was drawn from many walks of life.

The young men whose names were added to this memorial in 1921 had a range of occupations.

It’s true that most were employed either at the Works or the Locomotive Operating Department.

There were however a good few men from mining families – like Thomas Edwin Sayers or Henry Greener.

There were young men employed by the shops and merchants across the town – like Thomas Ingledew who was a confectioner or Samuel Longstaff Reeve, a clerk for a paper seller.

There were teachers, – like Joseph Huntson Atkinson, and George Crawford, some of whom had been brought to Shildon by their teaching career.

There were labourers

There were also a handful of career soldiers who had joined the army long before the war started.

The names that I gave there were just from the thirty men listed who died in that war – there are many other examples to be found.

This Institute was a place for anyone who wished to join and support it – whatever their background.

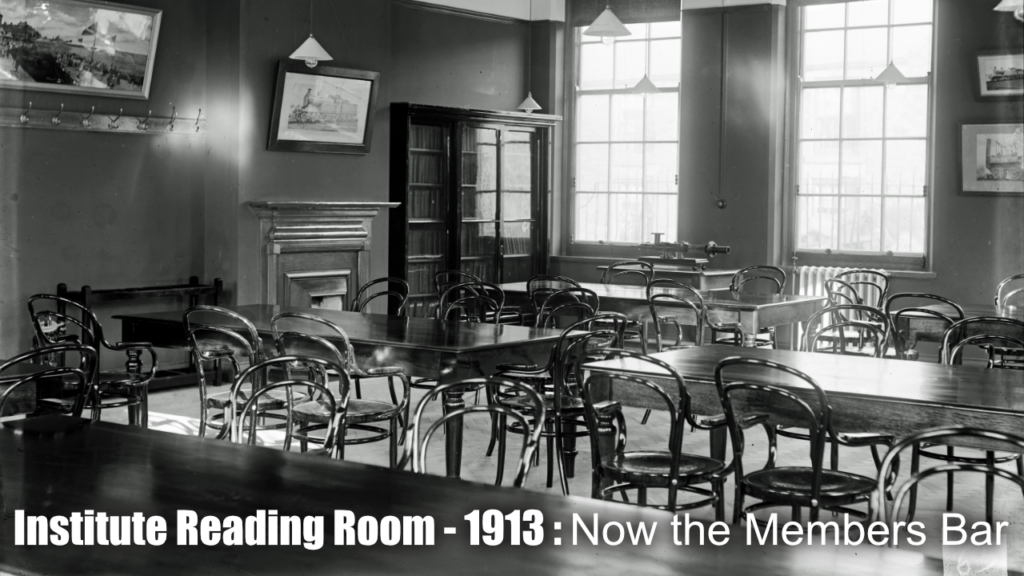

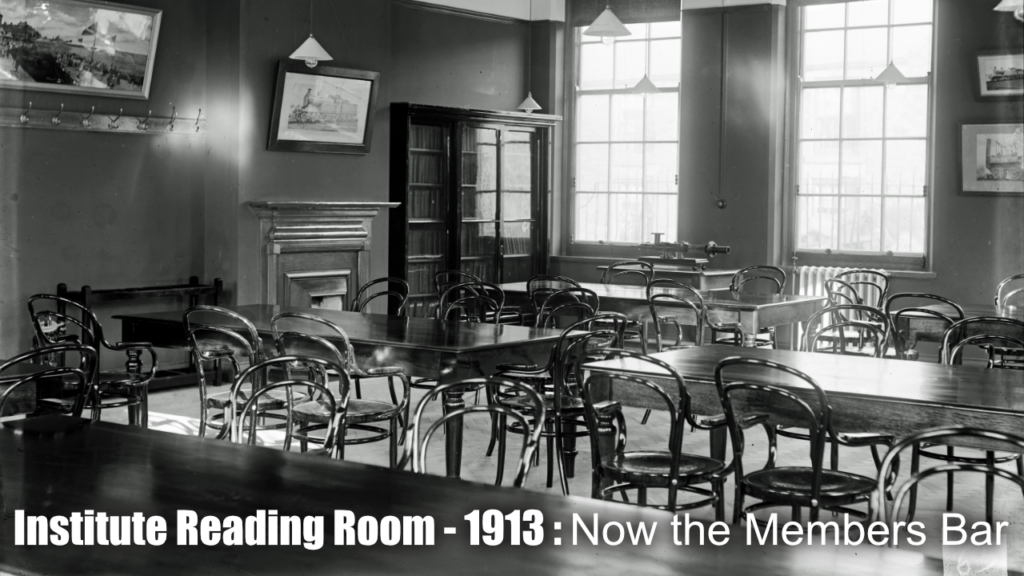

This was during days when it would still have been known for its lecture hall, its reading room and its extensive library as well as its leisure facilities.

There is no wonder that the town’s teachers were drawn to become members.

Just like William Denton, who was once an apprentice of Timothy Hackworth but became a world renowned Geologist and Daniel Adamson junior who was likewise and became a recognised engineer – both of whom were members of this Institute and both of whom acknowledged its role in taking them to new heights.

This is why it’s important for us, today, to similarly make the Institute a place for a range of people from this town and to find opportunities for them in doing so. It’s part of the DNA of the institute.

There are 250 stories that we have tried to uncover in our research.

Some of you know one or two of them – on account of being related and perhaps having been told about them through stories passed down in the family.

We want this Institute to know them all and for family members that weren’t told of the bravery of their relatives during this bloody, destructive and harrowing conflict – to be able to come here and know something of these men and women.

Our plan is to publish the research and then to invite contributions from families to tell us more. To tell us the things that the official documents never do about these very real human beings.

We will keep on updating this research for as long as there is something new to learn.

You can always access it via the Shildon Railway Institute website – or physically here at the Institute – and in both places there will be means to submit whatever else you know – which, with you permission we will add.

I want to share just one the stories with you.

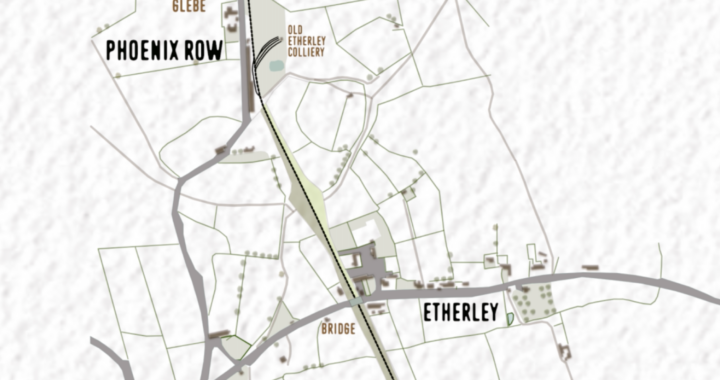

Alfred Graham was born in 1897at Brusselton. He was the son of John Graham and his wife Annie and was one of six children.

His father was an Engine Repairer and Fitter who had himself been born in New Shildon. In 1901 the family lived at 18 Victoria Street, a house built for New Shildon’s railway workers in the 1860s.

His father died while Alfred was a boy, leaving his mother to raise the family and the children in turn to support their mother.

By 1911 the family had moved to 2 Adamson Street, New Shildon, so of all the young men commemorated on the Railway Institute War Memorial, Alfred probably lived closest to the Institute itself.

He worked as a Shearer at the North Eastern Railway’s Shildon Works and had done so for five years before he enlisted. After the outbreak of the war, Alfred enlisted into the 9th Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps as a Rifleman with the regimental number 23279.

He gave his mother’s name as his dependent, with an address of 10 Adamson Street.

Arthur served with his unit on the battlefields in France.

In September of 1916 his battalion were in the vicinity of Dernancourt to the east of Amiens, camping to the south of Becordel.

On the 14th September the battalion received their orders for a big attach that was to be launched on the 15th with the co-operation of French troops, so on the 14th at 6:20pm they moved up to the Pommiers Redoubt, closer to the firing line.

The commanding officer recorded in his war diary that the men selected for the attack were veterans of the Somme and considered the “picked troops of the British Army” and that it was a great honour to have been selected for this attack.

He noted that “A new form of armoured motor car was employed for the first time driving this attack. They were known as ‘tanks’ and were able to move over any kind of rough ground, being able to cross shell holes or trenches, climb banks and get over sunken roads.”

In Arthur’s final hours of his life he would be among the first to witness the advent of tank warfare.

The battalion arrived at Montauban Alley at 5am on the 16th September where they supported the 43rd Brigade in an unsuccessful attach on Gueudecort before taking stock of their casualties.

They had lost 11 officers and 231 NCOs and other men. Among them was Rifleman Alfred Graham. He was only 20 years old when he was killed that day.

Alfred was buried in the London Cemetery and Extension at Longueval, Department de la Somme, Picardie on France. His death was reported to his work colleagues in the North Eastern Railway magazine.

____________

220 of the names on the memorial were of men who came back from the war – many to lead lives in Shildon.

But it’s right that they too should be remembered

Many brought home scars both physical and mental.

A few did not live long after the war having returned with medical conditions attributed to their service

____________

After the end of the war, in late 1918 with the British public was celebrating victory, the authorities begun to consider a problem closer to home. Housing.

Before the First World War slum housing had been an embarrassing issue. During it, thousands of men who lived in squalid conditions were rejected by the Army as not fit enough to fight.

Now hundreds of thousands of men were returning from the horrors of the Western Front expecting the country to reward them for their heroic efforts.

David Lloyd George’s government promised to provide ‘homes fit for heroes’ and under the Addison Act, his government put in place powers and funding for local authorities to take the lead in the matter.

The result was inventive new forms of building, stark modern styles and thoughtful town planning that shaped housing development for the rest of the 20th century

In Shildon this would lead to developments such as Dean Gardens, Southland Gardens, The Oval and Sunnydale.

We’ve been inspired by this Homes Fit for Heroes movement to start a new fundraising appeal phase for the Institute.

The main stairwell of this building is in a disgraceful and neglected condition.

We want to see it transformed back into a setting that befits being the home for this memorial.

The lads and lasses on this memorial are the heroes of this Institute – and we want to create a home fit for our heroes.

Most of the spruce up work we’ve done in the Institute so far has been things we can achieve with volunteer labour, but this is a task that will require both scaffolding and professional decorator skills.

So we’ve engaged three local decorators to provide quotes and straight away begin fundraising through our events and requests for donations toward this objective.

We hope that we can make this happen during the first half of 2022.

Thank you for listening.

I hope you all find what we have discovered interesting and we’ll look forward to any additional information that this community has that it is willing to share on these soldiers and nurses.

I also hope that you’ll enjoy what’s coming up next as author and historian Rob Langham has much to tell us about the North Eastern Railway in the First World War.